In June 1779, while most of the

Revolutionary War was focused in the southern

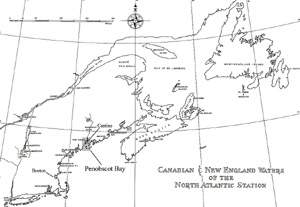

(Click image to enlarge)

An amphibious operation, the

expedition consisted of 40 vessels, nearly 2,000 seamen and marines, 100 artillerymen, and

870 militia. Mounting 350 guns, the sizable

fleet included 3 Continental Navy vessels, 3

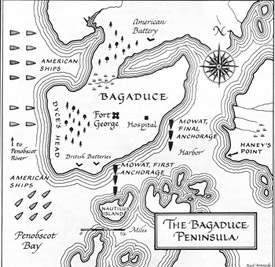

Reaching Castine (then called Bagaduce) on 25 July, the

Americans found only a modest earthworks situated in the peninsula’s center, a couple

of outlying redoubts, and the water approach to |

|

The

Americans' substantial momentum deteriorated quickly, however. Unable to convince

Saltonstall to engage the vastly inferior enemy fleet and clear the way for the land

forces to storm the garrison, Lovell and his inexperienced troops initiated a lengthy

siege. Conversely, Commodore Saltonstall refused to attack the enemy fleet with any

vigor, until Lovell had taken the bastion and one battery that overlooked the

harbor. Only a waist-high earthworks when the rebel flotilla arrived, Fort George

was unsuccessfully besieged by the American land and naval forces for over two weeks. By 13 August, the poorly coordinated siege of |

Of the utter confusion that followed, general Lovell

admitted that "...an attempt to give a description of this terrible Day is out of my

Power." Coordinating an effective stand grew increasingly difficult over the ensuing

days, as crews burned their vessels and took to the woods.

A handful of vain attempts were made to gather troops and make a stand, but

eventually, as Colonel Jonathan Mitchell of Maine revealed, all the participants made off

for home "...without any leave from a superior officer." Ultimately, all

American armed ships and transports, save for at least one captured by the British, were

destroyed along various portions of the river and upper bay, resulting in the greatest

American naval disaster prior to Pearl Harbor.

The expedition’s transport vessels, slower sailing merchant sloops and schooners, met

a particularly ignominious end after being left unprotected by the fleeing American

warships. With wind and tide against them,

most failed to ascend the river and were landed and burned by their crews to prevent

capture. Through maps, journals, and official

depositions, several expedition eyewitnesses described the transports’ retreat and

indicated the contingent’s final general location.

Historic documents indicate that nearly all of the expedition’s twenty-two

transport vessels were destroyed along the west bank of the

| The campaign, whose demise began in the earliest stages of its design, had ended in a spectacularly embarrassing turn of events for the state of Massachusetts. Ironically, British General Francis McLean was prepared from the outset for the fort to be taken, as the American forces before him and his naval counterpart Captain Henry Mowat appeared overwhelming. To an American spy within Fort George McLean divulged that he expected the fort to be overrun and "...only meant to give them one or two guns, as not to be called a coward." As the siege progressed, however, he considered every passing day (with the Americans' continued inactivity), "as good as another thousand men." With only two regiments of 700 soldiers McLean defended the fort successfully, while, with three sloops of war mounting only 50 guns, Captain Mowat stymied Saltonstall's larger fleet . |

In the aftermath, the Massachusetts General Assembly established a Committee of Enquiry and heard testimony from several high ranking officers. Commodore Saltonstall refused to testify before the Massachusetts inquiry by virtue of his position in the Continental Navy. Consequently, he escaped official discipline from the state of Massachusetts; the Continental Navy was less forgiving. After a court-martial held aboard the Continental frigate Deane, on 25 October 1779, he was dismissed from the service and later pursued the fortunes of privatering. Artillery Train Commander Paul Revere also suffered a blow to his reputation. His perceived arrogance during the campaign led to the collective scorn of his fellow officers and was the subject of lengthy depositions, but resulted in no official reprimand. Interestingly, after his character had been sufficiently impugned by those with whom he served, Revere requested his own court-martial in an attempt to clear his name. His request was not granted

|

It is

apparent that the failure of the Penobscot Expedition began well before the American fleet

first sighted the British garrison at Bagaduce. Despite the region’s considerable

resources and strategic value, the state of Massachusetts failed to develop a plan for

protecting the Penobscot until the advent of the British, and moreover, severely

overestimated their ability to expel the Britons once they had arrived. Additionally, the difficulties in obtaining

supplies, vessels, and manpower, were further exasperated by the inexperience of the

ground troops, and, to some degree, that of General Lovell himself. Moreover, the lack of homogeneity among the

vessels of the fleet doubtless led to problems of command.

Captains of the privateering vessels employed for the operation were clearly

unaccustomed to the realities of coordinated fleet actions, and were doubtless unwilling

to risk needlessly their most valuable asset, the vessel themselves. Finally, despite orders from the Massachusetts Council to “…at all times Study and promote the Greatest Harmony…between land and sea Forces,” the joint-command shared by Lovell and Saltonstall was sorely ineffective and due chiefly to the obstinacy of Commodore Saltonstall. His unwillingness to use decisively the superior American |

fleet, imperiled the expedition from the moment Bagaduce was within sight, and ultimately consummated the failure of the poorly executed operation. Indeed, while enamored over the recent exploits of John Paul Jones and the Ranger, Abigail Adams was not mistaken when she wrote on 13 December 1779, “Unhappy for us that we had not such a commander at the Penobscot expedition.” Arguably, such a man, admired for his decisiveness and courage, would have made a considerable difference.

Back Home To the Devereaux Cove Project fieldwork Image credits